A Basic Benchmark for Reasoning in Large Language Models

Cutting Through the Hype

I’ve generally been skeptical about the claims made about LLMs and their ability to reason. They’re certainly capable of many useful things, but it seems that much of the hype is based on a theoretical AI that does not yet exist. Talking heads across the board including the big AI companies, VC pundits, media interviews, entrepreneurs, and technical folk all quickly make the jump from the limited capabilities of today’s LLMs, to some future AI that will truly be a general replacement for human labour.

It should be noted that I’m referring to the raw abilities of LLMs. There are certainly many techniques you can layer over LLMs to overcome some of their limitations, but I care about the core capabilities of these systems, because I think they set a baseline that must be recognized and understood.

My own opinion has flip-flopped several times over the past year, but I think I’m now leaning more towards the view that Melanie Mitchell12, François Chollet3, Murray Shanahan4, Subbarao Kambhampati5, and other AI realists espouse – that we’re all tricking ourselves into thinking that LLMs are more than what they are through some combination of projection, anthropomorphization, and a Clever Hans effect6. We really want the AI of our dreams, so we’re quick to imbue LLMs with these capabilities, especially since they do truly demonstrate many useful traits. LLMs are also trained on vast amounts of data, so they are super-human in that sense. No one person can draw from that amount of knowledge, so of course LLMs seem intelligent to us. They are extremely well-read.

A Jagged Intelligence

More recently, people are understanding that we cannot compare the intelligence that LLMs demonstrate to human intelligence. Even through LLMs mimic human intelligence very well, it’s easy to forget that the underlying mechanisms are entirely different. This is now being called a “Jagged Frontier” or a “Jagged Intelligence” – AIs that seem to display human-level intelligence in some aspects, but fail miserably in other aspects178. Unlike human intelligence, where we can expect a baseline of generality and reasoning, LLM capabilities are unpredictable and they need to be verified empirically for each category of tasks we want them to perform.

One example of this kind of failure is simple to demonstrate. LLMs, despite all their surprising abilities, are poor at counting. They cannot reliably count paragraphs in articles, words in paragraphs, or even letters in words. Even the state of the art LLMs cannot perform this task consistently. For example, if you ask an LLM “How many times does the letter ‘r’ appear in the word ‘barrier’?”, there’s a good chance it will respond with “There are two ‘r’s in the word ‘barrier’.”

It’s not difficult to guess why LLMs fail at this task. LLMs are feed-forward systems that process text in chunks. Although they can understand the gist of an instruction through concepts they form in their neural hierarchies, they do not construct plans for carrying out instructions, nor do they have a working memory to perform tasks like counting the way humans do. Instead, LLMs draw from the vast number of examples they are trained on, and they interpolate through those examples to produce an approximate retrieval9 of an answer to a prompt.

An answer like “There are two ‘r’s in the word ‘barrier’.” is also understandable when you think about LLMs as systems that are designed to mimic human responses. It’s not hard to imagine that there exist spelling corrections on the Internet, and in the LLM corpus, where one person corrects another, reminding them that there are two ‘r’s in the word barrier, because it is implicit that “barrier” ends with an ‘r’, so of course we humans focus in on the ‘r’s in the middle of the word and remind each other that, “actually barrier has two ‘r’s in it”.

Although these failures are understandable in retrospect, they can be surprising when you’ve convinced yourself that LLMs have human-level or super-human intelligence. Nonetheless, we should not simply overlook these failures as quirks or trivial examples because they reveal a core difference in intelligence that optimists should be aware of.

Letter-Counting as a Benchmark for Reasoning

We have a plethora of benchmarks that we test new LLMs with – general knowledge tests (MMLU), math tests (MATH), and common sense tests (HellaSwag). We’ve become used to seeing these benchmark names and acronyms in LLM release announcements but they all feel quite opaque to me. What are they actually testing, how reliable are they, and what do they signify from a human point of reference?

This letter-counting test feels much more approachable to me. It’s immediately apparent that humans can perform this task at close to 100% accuracy, and that an LLM would need to have some baseline of reasoning capability to perform it reliably and in a generalized manner.

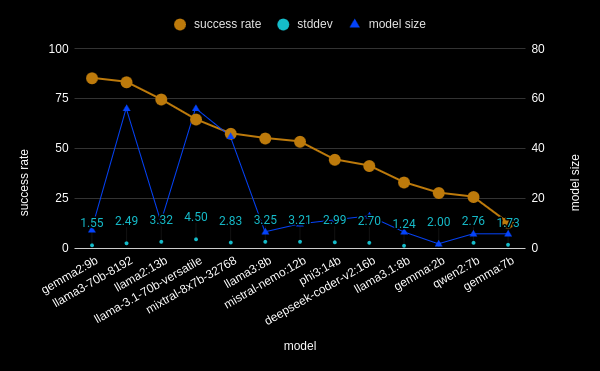

To that end, I sought to benchmark various LLMs with this test, and wrote some code10 to do so. Using ollama11 and groq12, I tested several open-source LLMs, measuring their ability to count repeated letters in random words, sampling each LLM several times to measure their accuracy, along with a standard-deviation measurement.

Specifically, the prompt is:

How many times does the letter "L" appear in the word "WORD"?

Respond with JSON in the format { "count": N }

The results are as follows:

| runner | model | success rate | stddev | model size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ollama | gemma2:9b | 68.24 | 1.55 | 9 |

| groq | llama3-70b-8192 | 66.67 | 2.49 | 70 |

| ollama | llama2:13b | 59.68 | 3.32 | 13 |

| groq | llama-3.1-70b-versatile | 51.66 | 4.50 | 70 |

| groq | mixtral-8x7b-32768 | 46.00 | 2.83 | 56 |

| ollama | llama3:8b | 44.08 | 3.25 | 8 |

| ollama | mistral-nemo:12b | 42.72 | 3.21 | 12 |

| ollama | phi3:14b | 35.52 | 2.99 | 14 |

| ollama | deepseek-coder-v2:16b | 33.04 | 2.70 | 16 |

| ollama | llama3.1:8b | 26.40 | 1.24 | 8 |

| ollama | gemma:2b | 22.16 | 2.00 | 2 |

| ollama | qwen2:7b | 20.56 | 2.76 | 7 |

| ollama | gemma:7b | 10.24 | 1.73 | 7 |

This demonstrates several interesting findings. Firstly, even the best models cannot perform the task reliably. Benchmarks like this are important since you’d be tricked into thinking that an LLM had this capability if you tested it by hand. Secondly, when it comes to LLMs, bigger is not always better, depending on the task. This is Jagged Intelligence in plain sight. gemma2:9b performs better than the state of the art llama-3.1-70b-versatile which is almost 8x bigger, and oddly gemma:2b is 2x better than gemma:7b. Evidently, adding more parameters or more training data into the mix can sometimes cause LLMs to regress in basic capabilities.

There are certainly more directions you could take with a benchmark like this. I might continue to test it against the latest cloud-based LLMs (GPT-4o, Claude Opus, Gemini Advanced, etc.). I chose to use local LLMs for the most part, because, similar to the ARC Challenge13, I think it’s important to measure LLMs that aren’t entirely opaque and can be run independently to ensure there aren’t extra factors at play. Another obvious next step would be to prompt engineer the task to see what gains you could scrape out of it.

Be Informed, Stay Skeptical

Even if you’re a proponent of the benefits of AI or LLMs, it behooves us to know their limitations well, so that we can utilize them effectively. Perhaps we are on the cusp of AGI, but I think the breakthroughs required to go from today’s LLMs, to machines that can truly reason are not so obvious. Only time will tell if we’re in for a hard takeoff, or another AI winter. It’s important to sharpen our skeptical minds when we’re immersed in a hype bubble. We need to catch ourselves when we make those quick but giant leaps between what we have at hand, to the future we all dream of.