How Much Energy Does Local AI Use?

How Can We Understand the Costs of Local AI?

Although cloud-based AI services like OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Microsoft’s Copilot dominate the AI space, local LLMs have also become a popular alternative, especially for those who are tech-savvy or privacy-conscious. Inference engines like Ollama1, LM Studio2, and llama.cpp3 are popular and widely supported by other tools in the ecosystem.

For computers that are capable enough, these engines can use the available processing power and graphics hardware to run LLMs as fast as possible. The capabilities of local LLMs are certainly limited, but you gain the freedom to use them as much as you like without paying the token cost that cloud providers set, which is increasingly important for the token-hungry agentic workflows that are all a buzz.

It’s easy to think that these local AIs are essentially free, aside from the initial cost of the required hardware, but what impact might they actually have on our electricity usage, and how do we relate that consumption to things we are more familiar with?

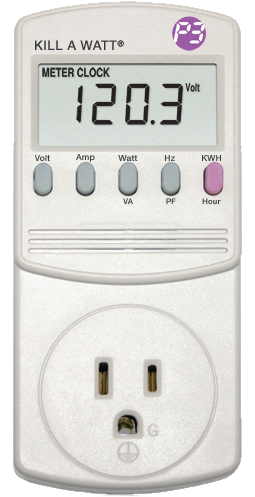

I took the time to understand this using an actual electricity usage measurement tool, the “Kill A Watt” electricity monitor made by P3 International4.

Setting a Baseline

Here in Canada we pay about 16.5 cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh) for our electricity on average, though rates vary across provinces5. The typical household uses about 900 kWh per month, which amounts to a bill of about $150 CAD, or $110 USD. I have a modern refrigerator that I measured, and it only consumes 0.78 kWh in 24 hours, or $0.13 CAD a day, $3.90 a month. I also measured my kettle at 1340 watts while boiling 500ml of water (about 2 cups), but that only takes about 3 minutes, which adds up to 0.07 kWh, or $0.012 CAD. A typical LED light bulb will consume 9 watts of electricity which adds up to 0.144 kWh if left on for 16 hours a day, or $0.024 CAD a day, $0.72 a month. These are relatively small costs, but they add up, and household’s usage is usually dominated by water heating, space heating or cooling, and washer/dryer usage.

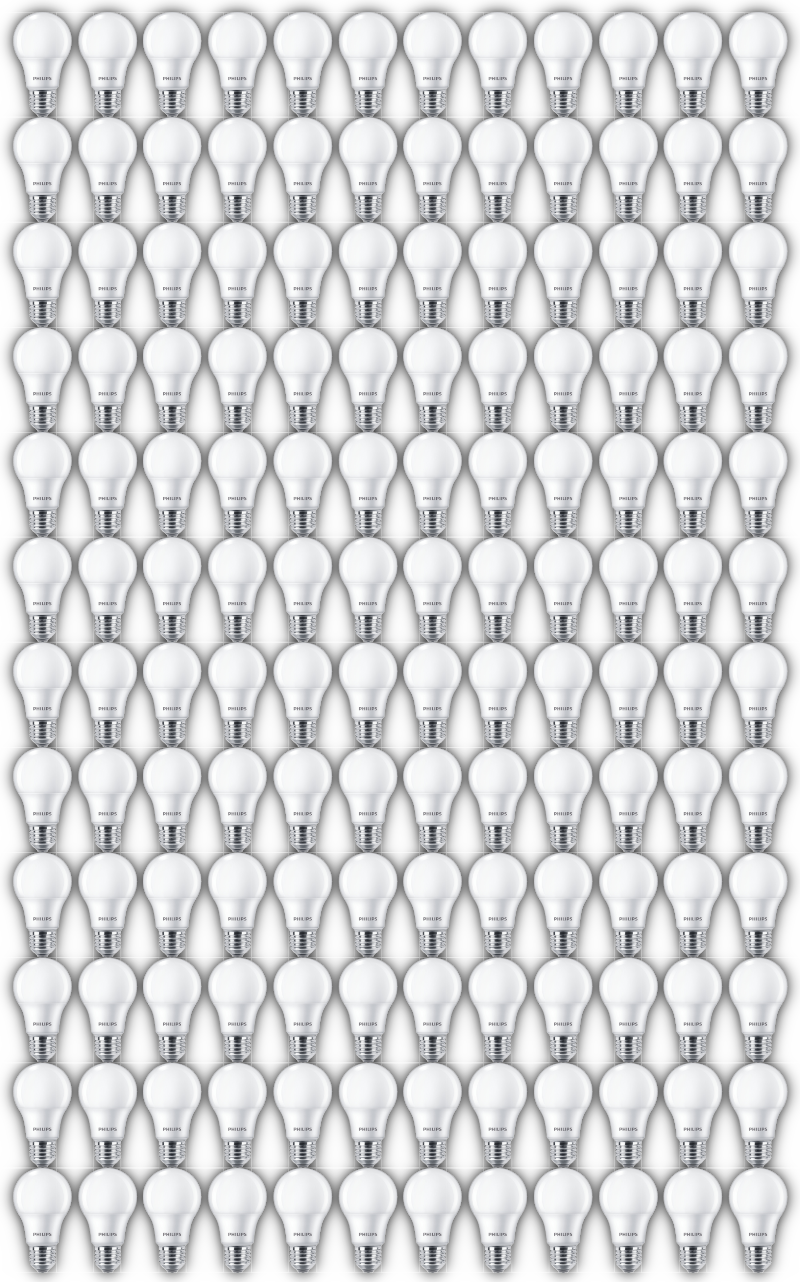

Though all of these watt and dollar numbers give us a general sense of the cost of appliances, it may be most useful to think about energy usage in terms of light bulbs, since they are the most visual form of electricity use. A typical modern LED light bulb is very efficient. It converts 90% of those 9 watts into light. If we imagine a grid of 12 by 12 light bulbs (144 in total), and we turn that grid on for 3 minutes, that’s almost equivalent to boiling 2 cups of water.

I also wanted to measure typical PC energy usage as a baseline while idle, watching a video, or playing games. Here are those numbers:

| Scenario | Watts | Equivalent # of light bulbs | CPU Usage | GPU Usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idle Windows PC with no significant applications running | 46 | 5.1      | 0 | 0 |

| Watching a YouTube video, fullscreen at 1080p | 56 | 6.2       | 2 | 5 |

| Playing Overwatch at 1080p, high quality graphics | 112 | 12.4             | 15 | 30 |

| Playing Diablo 4, in “Performance” mode | 168 | 18.7                    | 55 | 39 |

Measuring Local AI

With this in mind, I set out to measure a set of LLMs running under Ollama, using the Kill A Watt monitor. I ran these tests on my desktop PC, running Windows 10, with a Nvidia RTX 4070 Ti with 12GB of video RAM, and an Intel i7-4790K CPU with 4 cores. I gave the models the task of translating text, 900 words extracted from a public domain book from Project Gutenberg, from English to French.

# Using Ollama to run this task with each model,

# injecting the sample text into the command before the prompt.

ollama run <model> "$(cat sample.txt)" Translate to French

| Model | Watts | Equivalent # of light bulbs | Time (seconds) | CPU Usage | GPU Usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| granite3.3:2b | 265 | 29.4                              | 7.24 | 15 | 95 |

| gemma3n:e4b | 246 | 27.3                            | 19.52 | 25 | 90 |

| qwen3:8b | 280 | 31.1                                | 24.13 | 19 | 100 |

| glm-4.7-flash:q4_K_M | 130 | 14.4               | 294.54 | 34 | 50 |

Monetarily speaking, these simple tests are just fractions of a cent, but I do find it useful to think about the energy cost of this task as the equivalent of turning about 20 LED light bulbs on for about 30 seconds, depending on which model you happen to use. With agentic workflows taking many minutes, or even hours, you can imagine the energy usage racking up.

Thinking in Externalities

One of the side effects of running AI locally is that the energy impact becomes more direct and apparent. Anyone who has done serious work with local AIs will know that their PC effectively turns in to a space heater, since CPUs and GPUs give off a lot of heat when they are pushed to their limits, and most models utilize 90+% of a GPU’s processing power.

Even then there are externalities to consider. If local AI usage were far more common, households could see increasing electricity use over time, putting a strain on power grids or increasing demand and electricity rates, as we’ve already seen in U.S. cities with new data centres6. Then there’s the matter of the source of this energy. Most of Canada is fortunate to have a large supply of hydroelectric and nuclear power, but your state or city may not be so lucky.

We’re so used to cloud services now, that we don’t think twice about the energy impact of using a website or app. The trade-off was reasonable with conventional software, based on well-optimized algorithms. But AI flips that trade-off on its head as we seek dubious productivity gains with AI models that are inherently power hungry. This effect is multiplied by the big AI companies hiding or subsidizing the true cost of their operations. Despite the enormous valuations and billions being thrown around, OpenAI is expected to run out of money in 18 months7.

It’s difficult to do, but when we use AI we ought to integrate these externalities into our mental models. The energy cost, the copyright lawsuits, the exploited data workers8, AI psychosis, and even the AI-washing layoffs9. The rapid rate of adoption has already exceeded our ability to keep up with the downsides.

The next time you use AI, maybe imagine a bank of light bulbs being turned on for the duration of your query in some anonymous data centre on the outskirts of your city.